Overview

The black and white ruffed lemurs is one of the most iconic species of lemur, with its distinctive black and white patterning. A large white ‘ruff’ of fur around their neck gives them their name.

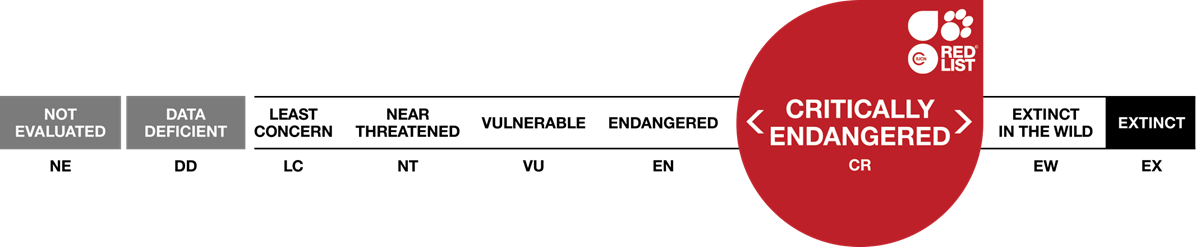

They are also one of the most endangered lemur species, classified as critically endangered, meaning they are one step away from being extinct in the wild.

All about us

| Distribution: | Eastern Madagascar |

|---|---|

| Habitat: | Lowland forests |

| Height: | Body length 50cm to 55cm, tail length 60cm to 65cm |

| Weight: | 3kg - 4.5kg |

| Lifespan: | In the wild 18 to 20 years, in captivity 20 to 25 years |

| Threats: | Main threats are habitat loss, and capture for the meat trade |

Scientific name: Varecia variegata

Here at Woburn there is a small group of male black and white ruffed lemurs that live alongside the ring-tailed lemurs and red-bellied lemurs in the Foot Safari. Some members of this group belong to a sub-species of black and white ruffed lemur called white-belted ruffed lemurs. They look slightly different and have a greyer face, but are also Critically Endangered.

They are the most relaxed of our lemur species and are most often found sunbathing or sleeping. Their loud call can be heard throughout the park.

black and white ruffed lemur facts

- Physical features

- Diet

- Social structure & communication

- Husbandry and enrichment

- Threats & conservation

The black and white ruffed lemur is one of the larger species of lemur, and the largest member of its family the Lemuridae. They have a distinctive black and white coat of thick fur, and a ‘ruff’ of fur around the neck.

They are agile climbers, with hands similar in structure to a human hand, including an opposable thumb, allowing them to grip when climbing and to hold objects. Their back feet feature a large modified big toe allowing them to grip with their hind feet just as easily.

They have a long thick tail, which although not prehensile, it is vital for balance when climbing and jumping, and is longer than their body length.

Lemurs have a much more developed sense of smell than other primates. They have an enlarged Jacobson’s organ, a sensory organ in their nose which allows them to read pheromones and other chemicals. Scent marking is an important behaviour for the ruffed lemur, using scent glands located in the chest, neck, and muzzle, to mark out territories.

Ruffed lemurs are one of the most vocal species, with a call said to be the second loudest of all primates, only slightly less than howler monkeys. They have a series of growls, barks, and howls to help communicate predator alarm calls, territorial calls, and mating calls amongst other things.

The ruffed lemur is mostly diurnal and active during the early morning and late afternoon, using the cooler parts of the day to forage for its food.

They will eat a diet of fruit, seeds, leaves, and nectar. The ruffed lemur has a particular taste for nectar, using its long tongue and tapered snout to reach inside flowers for it. This taste for nectar has lead them to develop a crucial relationship with the traveller’s tree, a tall palm-like tree topped with a single vertical fan of large leaves. They are strong enough to pull open bracts, tough scales of bark, which hide flowers within, and drink their nectar. As they drink the plants pollen sticks to their fur, and is carried by them to the next plant. As a result they are a pollinator for the traveller’s tree, and are thought to be the largest pollinator in the world.

Ruffed lemurs can have varying group sizes, but generally up to 30 individuals are in a group with multiple males and females. As with most lemur species, the females are dominant and will defend their territories with loud calls and scent marking.

Grooming is an important group bonding tool, using specialised teeth they will groom each other to establish bonds and care for their thick coats.

Ruffed lemurs are one of few primates to build a nest. Most species carry their young on their backs, however ruffed lemurs build a nest which allows them to have two to six offspring at a time, giving birth in the nest, and then leaving the young there for the first few months until they are big enough to be carried in the mother’s mouth. All of the group will participate in caring for the young, who are weaned at around four and a half months old and are close to full size by six months of age.

In the wild, lemurs would be found up in the mid canopy of the trees, very rarely on the ground. To allow them to mimic this natural behaviour their enclosure is designed with large trees to traverse, and ropes connecting different areas. The lemurs use these ropes and branches to manoeuvre around the enclosure, promoting exercise, and demonstrating their natural climbing and jumping abilities when doing so.

Wild lemurs will spend most of their day foraging for food. To mimic this, and to keep our lemurs active, we spread their feeds throughout the enclosure, hiding food, placing it high up, making it hard to reach, and changing our feeding locations daily to keep them on their toes.

Lemurs are a small brained and are a less intelligent group of species, so we have to make sure our enrichment isn’t too complicated, for example hiding food in puzzle feeders may prove too difficult for them to figure out.

Madagascar can have changing weather, from rain to severe heat and so the lemurs are adapted to both, but we give them a heated house all year round, with the option to venture into the cold, to mimic the temperature range in Madagascar.

The ruffed lemur has few predators due to its large size, but the largest carnivore in Madagascar, the fossa, is its main killer, they are expert climbers and so a deadly predator to most lemur species.

The main threat to lemurs is habitat loss, due to slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and mining. This destroys habitats, and vital forest corridors which allow groups to move between locations. Almost 90% of the natural forest in Madagascar has been destroyed since human habitation of the island.

The ruffed lemur is one of the most heavily hunted species due to their size and the fact they are diurnal. Their meat is one of the most expensive and prized meats, and so it is one of the first species to disappear from an area when humans move in.

There are a number of national parks and protected regions of Madagascar, some of which are within the ruffed lemurs range; however poaching is still a threat, even in these protected areas.

Although a large amount of conservation work is going on there is still a lot to do in terms of educating the people to the plight of all lemur species, and recovering the habitat before reintroduction can be a viable option. There are several conservation projects ongoing in Madagascar, including education projects, habitat repair, and eco-tourism. Some reintroductions of captive bred lemurs have been trialled in the past, but with mixed results.

They are part of an EEP, the European Endangered Species Programme. The EEP is the most intensive type of population management for a species kept in European zoos. Each EEP has a coordinator, who is assisted by a Species Committee. They are responsible for collecting all the data on births, deaths, and transfers, carrying out demographical and genetical analyses, and producing a plan for the future management of the species. Together with the Species Committee, recommendations are made each year on which animals should breed or not breed, which individual animals should go from one zoo to another, and so on.

The black and white ruffed lemur is listed as a CITES category I species, meaning the movement of this species is greatly controlled and restricted, trade in specimens of these species is permitted only in exceptional circumstances.